Another life well-lived. And although Tony Hillerman will be remembered, quite rightly, for his mystery novels, the passage that sticks with me comes from his memoirs, describing an incident during his early post-war life as a reporter:

I was talking to a young Texas highway patrolman one morning outside the Stinnett Courthouse when his radio buzzed him. A double fatality on Highway 206 about 12 miles north. He roared away. I followed. A Packard sedan had collided head-on in about the center of the two-lane highway with some sort of pickup truck. The remains of the truck were scattered in the roadside wheat field. The sedan was still on the pavement, its front end back to the instrument panel missing. The body of the driver was in his seat, his head impaled on the steering post, blood, teeth and tissue splashed everywhere. The highway patrolman backed away from this, unable to control his nausea. I remember standing there untouched, guessing at the combined speeds, noticing how the wheel rim had gouged a rut in the concrete, collecting the details I'd need for my story, finally aware the patrolman, still pale and shaken, was looking at me as if I was something less than human. And all I could say to explain it was that it's not so bad when the dead are not your friends.

The shrinks had not yet invented post-combat trauma syndrome but I suppose that's the name for it — for the accumulation of baggage we sometimes talk about even now when what's left of Charley Company has its annual reunion. We mention the recurrence of old nightmares, of how long it took us to get rid of chronic moments of “morning sickness,” but we hardly ever discuss this incurable numbness. A deep, deep burn costs one the feeling in a fingertip. Perhaps seeing too much ghastly casual death does it to a nerve somewhere behind the forehead bone.

Links: here I muse over one of Hillerman's Jim Chee novels. Here I report back on his memoirs, which, though memorable, desperately needed an attentive copy editor.

“he”/“him” A Canadian Prairie Mennonite from the '70s & '80s, a Preacher’s Kid, slowly recovering from a hemorrhagic stroke. I am not — yet — in a 12-Step Program.

Friday, October 31, 2008

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

A Life Well-Lived

After the last post I received inquiries into my father in law's state. He passed away this morning in a moment that, by the nurse's description, sounds as if it was quite peaceful.

Thank you all for your comments, thoughts and prayers. It seems fitting I link back to this post in which I contrasted his life with Hugh Hefner's, and wondered whose life was richer.

Thank you all for your comments, thoughts and prayers. It seems fitting I link back to this post in which I contrasted his life with Hugh Hefner's, and wondered whose life was richer.

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

Swordfishtrombones (33 1/3 Series) by David Smay

We have become a driving household. Six weeks ago my father in law was taken to the hospital. He has since been moved to palliative care. Combine this with the usual school events and ringette games and the family schedule, such as it is, gets thrown seriously out of whack.

These events alter the reading habit too. A friend of mine once told me he'd read a bunch of John Irving novels while his wife underwent a series of critical operations. Now that he and his wife were on the other side of that health crisis, he couldn't remember anything about the novels, except that he had no trouble following their plots.

I'm not quite that preoccupied, but even so Continuum's 33 1/3 books are a very welcome alternative to choosing between "heavy lifting" novels and mysteries. They are wee things: roughly 4" X 5", 125 pages or so. They fit easily into jacket pockets, and look as if they were built to accompany the CDs of the albums they dissect and laud. They are written and published for people (guys, mostly) for whom the liner notes are never enough.

I'm not quite that preoccupied, but even so Continuum's 33 1/3 books are a very welcome alternative to choosing between "heavy lifting" novels and mysteries. They are wee things: roughly 4" X 5", 125 pages or so. They fit easily into jacket pockets, and look as if they were built to accompany the CDs of the albums they dissect and laud. They are written and published for people (guys, mostly) for whom the liner notes are never enough.

There are now over 60 of these books, and I had trouble deciding where to start. On the face of it my choice of Tom Waits' Swordfishtrombones by David Smay (A) was almost counterintuitive. I don't mind Waits in small doses -- on a mixed tape, or a "various artists" CD -- and I'm sure a concert would be an event worth the price and logistics of attending (certainly the movie was worth it). But it's rare that I bother myself with an entire album's worth of his material. Tom Waits fans are frequently Neil Young fans, and both performers start with the roadblock: Folks, you didn't come here to listen to something "pretty," so brace yourselves and let's go.

So why bother at all? I wasn't sure, but I dozily read through the first 25 pages in which Smay recounts Waits' preoccupation with the freakish, his determination to control his musical legacy, his stubborn streak and litigiousness when it comes to advertisers, and how advertisers would still give anything to get a little Waits' sound behind their corn chips and automobiles, and gradually I found myself compelled to accept Smay's own thesis: "Maybe Carnivale's creator never listened to Tom Waits -- doesn't matter. Because that vision that Tom created moves and breathes in the world now ... the Tom Waits Carnival is part of our common currency."

Damn. He's right!

I doubt I'll spring for another 60 titles, but I'm sure my 33 1/3 library is bound to get larger. If Continuum would like, I've even got a proposal for Jason & The Scorchers' Thunder & Fire (A), linking its underlying narrative to the preaching of Qoheleth in Ecclesiastes. I'm cheap, too: Will Write For Books.

Links: the 33 1/3 blog, my post on Jason & The Scorchers.

These events alter the reading habit too. A friend of mine once told me he'd read a bunch of John Irving novels while his wife underwent a series of critical operations. Now that he and his wife were on the other side of that health crisis, he couldn't remember anything about the novels, except that he had no trouble following their plots.

I'm not quite that preoccupied, but even so Continuum's 33 1/3 books are a very welcome alternative to choosing between "heavy lifting" novels and mysteries. They are wee things: roughly 4" X 5", 125 pages or so. They fit easily into jacket pockets, and look as if they were built to accompany the CDs of the albums they dissect and laud. They are written and published for people (guys, mostly) for whom the liner notes are never enough.

I'm not quite that preoccupied, but even so Continuum's 33 1/3 books are a very welcome alternative to choosing between "heavy lifting" novels and mysteries. They are wee things: roughly 4" X 5", 125 pages or so. They fit easily into jacket pockets, and look as if they were built to accompany the CDs of the albums they dissect and laud. They are written and published for people (guys, mostly) for whom the liner notes are never enough.There are now over 60 of these books, and I had trouble deciding where to start. On the face of it my choice of Tom Waits' Swordfishtrombones by David Smay (A) was almost counterintuitive. I don't mind Waits in small doses -- on a mixed tape, or a "various artists" CD -- and I'm sure a concert would be an event worth the price and logistics of attending (certainly the movie was worth it). But it's rare that I bother myself with an entire album's worth of his material. Tom Waits fans are frequently Neil Young fans, and both performers start with the roadblock: Folks, you didn't come here to listen to something "pretty," so brace yourselves and let's go.

So why bother at all? I wasn't sure, but I dozily read through the first 25 pages in which Smay recounts Waits' preoccupation with the freakish, his determination to control his musical legacy, his stubborn streak and litigiousness when it comes to advertisers, and how advertisers would still give anything to get a little Waits' sound behind their corn chips and automobiles, and gradually I found myself compelled to accept Smay's own thesis: "Maybe Carnivale's creator never listened to Tom Waits -- doesn't matter. Because that vision that Tom created moves and breathes in the world now ... the Tom Waits Carnival is part of our common currency."

Damn. He's right!

I doubt I'll spring for another 60 titles, but I'm sure my 33 1/3 library is bound to get larger. If Continuum would like, I've even got a proposal for Jason & The Scorchers' Thunder & Fire (A), linking its underlying narrative to the preaching of Qoheleth in Ecclesiastes. I'm cheap, too: Will Write For Books.

Links: the 33 1/3 blog, my post on Jason & The Scorchers.

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

"Deeper" vs. "Urgent" Questions, vis-à-vis Milan Kundera

I heard an interview with one of the founders of London's School Of Life, a place that promises curious fun (home). She described the meals they hold, and among the questions "tabled" is: "When did you realize you were no longer a child?" My initial reaction to that question was, "I hope I am becoming more childlike (as opposed to childish) all the time!" After some consideration of Milan Kundera's past, however, I realized that there is at least one identifiable moment when I understood I was no longer a child: when I comprehended that most, if not all, of my favorite writers were anything but paragons of virtue.

I'm told the Cubans have a saying: "There are only two sorts of citizens: the innocent and the living." Certainly that is a motif that runs through the literature of dissident writers who witnessed Communism firsthand. This is not an uncommon motif in Western fiction either -- and properly so. Even so, revelations like these pose difficulties for readers who love their writers through their work.

Richard Byrne says, "The deeper question ... is how the reader should assess Kundera's approach to many of his pet themes -- memory, betrayal, and the defense of history against the violence done to it by our political leaders East and West." The Anabaptist Confessional side of me is surprised that Kundera's (and Grass's) "approach" wasn't more direct: begin with the worst of who you are, and proceed from there via concentric circles until you've worked out your salvation with fear and trembling, and the odd unexpected measure of grace. Of course, the fearful drunkard in me understands all too well why this approach is to be avoided at all costs.

Milan, Milan: God be with 'im, the poor sod. And perhaps while we're all pondering the deeper question we can address the more urgent one: how do we put a stop to our nation's policy and practice of torture?

I'm told the Cubans have a saying: "There are only two sorts of citizens: the innocent and the living." Certainly that is a motif that runs through the literature of dissident writers who witnessed Communism firsthand. This is not an uncommon motif in Western fiction either -- and properly so. Even so, revelations like these pose difficulties for readers who love their writers through their work.

Richard Byrne says, "The deeper question ... is how the reader should assess Kundera's approach to many of his pet themes -- memory, betrayal, and the defense of history against the violence done to it by our political leaders East and West." The Anabaptist Confessional side of me is surprised that Kundera's (and Grass's) "approach" wasn't more direct: begin with the worst of who you are, and proceed from there via concentric circles until you've worked out your salvation with fear and trembling, and the odd unexpected measure of grace. Of course, the fearful drunkard in me understands all too well why this approach is to be avoided at all costs.

Milan, Milan: God be with 'im, the poor sod. And perhaps while we're all pondering the deeper question we can address the more urgent one: how do we put a stop to our nation's policy and practice of torture?

|

| "Except in accessories." |

Tuesday, October 21, 2008

Monday, October 20, 2008

The Crystal Cave by Mary Stewart

When I was in late adolescence I read several paperback versions of the Arthurian saga. Most of these were camp, usually with a slightly pornographic bent. They were all fun, but offered very little insight into what prompts humans to make wise or disastrous choices of far-reaching consequence. When I got to university I asked a friend who was immersing himself in Arthurian narratives to recommend a particular writer. He covered the gamut from T.H. White’s purely naturalistic approach (A) to some of the wilder “bibbety-bobbity-boo” magick-fests. “Mary Stewart strikes a balance between the two. Her Merlin is in the grip of some sort of supernatural impulse, but it isn’t magic wand stuff. I’d probably recommend her Merlin books over just about anyone else’s.”

Re-reading The Crystal Cave some twenty years later, I think my friend’s analysis was right on the money. Stewart introduces Merlin as a young, conniving bastard with an appetite for eavesdropping. He is a pitiable figure — picked upon, beaten and targeted for a courtyard assassination. But occasionally something seems to take hold of him and show him the true shape of things. He cannot summon this ability, but it visits him at crucial moments.

Already prone to manipulating people’s fear of him, he learns to exploit these moments with increasing confidence. By book’s end he is a cocky young man, gleefully assisting the newly crowned Uther in his midnight tryst with Lady Ygraine, an adulterous romp that will result in the birth of Arthur — and the New Beginning for England.

400-plus pages leading up to the conception of Arthur might seem like an indulgence in another writer’s hands, but Stewart ably demonstrates why her Arthurian account is still the first choice of geek (or any other) readers everywhere. Her pre-Arthurian England is mash-up of Christian and pagan sects vying to hold political sway over the country's itinerant warlords. Merlin is a skeptic of both religions, but has a shrewd sense of how the two collude. Above all he is a pragmatist with a sense of destiny, and he appeals to one or the other wherever they serve his purpose.

Someone once equated writing a novel to “juggling confetti” and in this regard Stewart has few peers. There are several strains of political intrigue running through these novels, and she has a clear sense of where they all lead, but only reveals what she has to in order to sustain reader interest. Again, this is meat and potatoes geek material, but she serves it up with considerable panache where someone like, say, Neal Stephenson sometimes struggles. In Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle an all too frequent narrative pattern was an unanticipated wallop of unexplained significance, followed by a buffering scene, followed by an episode that revealed what the wallop was all about. Stewart is a gentle massager of foreshadowing, giving the reader a sense of how and why a particular character is developing a moral blind-spot which will eventually be exploited to tragic effect. When surprises occur they do not materialize out of thin air, and thus have genuine emotional weight.

My 37-year-old copy of this book fell apart on my second reading, so I visited the nearest used bookstore and picked up replacements for all three titles. Is there a used bookstore that doesn’t have these books on hand? Go and find out. If you’re an Arthurian buff who hasn’t yet read Mary Stewart, you’ll thank me for introducing you to such cheap but enduring thrills.

(And of course there is always Amazon.)

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

Tuneage

Last month's musical selections were such a treat, I hesitate to turn the odometer. A quick summary:

Fate by Dr. Dog. I hadn't heard of these guys until DV assured me they are all the rage among the younger crowd, particularly in Philly. Despite my initial misgivings, I quickly became fond of Fate. I won't try to emulate this guy's Bangsian endorsement (I'm not that enthusiastic of the disc, for one thing): better just to resort to lazy typifying. Dr. Dog gains their musical traction via the disciplined harmonic experimentation The Beatles liked to do, coupled with the lyrical and percussive play the Talking Heads enjoyed. My daughters found the overarching effect a little melancholy, but nowhere near to the degree of an act like Wilco (I confess I don't really get those guys). Best Heard: while prepping food on a sunny afternoon (e, A).

Fate by Dr. Dog. I hadn't heard of these guys until DV assured me they are all the rage among the younger crowd, particularly in Philly. Despite my initial misgivings, I quickly became fond of Fate. I won't try to emulate this guy's Bangsian endorsement (I'm not that enthusiastic of the disc, for one thing): better just to resort to lazy typifying. Dr. Dog gains their musical traction via the disciplined harmonic experimentation The Beatles liked to do, coupled with the lyrical and percussive play the Talking Heads enjoyed. My daughters found the overarching effect a little melancholy, but nowhere near to the degree of an act like Wilco (I confess I don't really get those guys). Best Heard: while prepping food on a sunny afternoon (e, A).

Universal United House of Prayer by Buddy Miller. This is a spinach 'n grits album — it's delicious, but has a robustness that can be unsettling. Miller opens the album with a Mark Heard song that pretty much sums up the last eight years (well ... the last 30, really) of my life: “Worry Too Much.”

It's the quick-step march of history

The vanity of nations

It's the way there'll be no muffled drums

To mark the passage of my generation

It's the children of my children

It's the lambs born in innocence

It's wondering if the good I know

Will last to be seen by the eyes of the little ones

Miller launches from here into a sincere exploration of his faith, the parameters of which are familiar — and discomfiting — to me. Miller's vehicle of choice is what Pappy O'Daniel calls “Old Timey Music”: I do love this disc, but find it difficult to listen to. The songs, the sentiment and dare I say the faith are all sturdy enough to deliver Miller from the present crucible of life, but I could have done with just a dash of “O'Daniel's” conniving guile. A little whisky makes the preaching easier to ingest. Best Heard: when tempted to YouTube Sarah Palin (e, A).

Lost In The Sound Of Separation by Underoath. Metal has splintered into so many different discordant shards I have a very difficult time keeping track of what's worth listening to. Unless a friend passes along a disc, or Metacritic tabulates a particularly high mark, I don't even bother with the genre. Underoath qualifies in the latter instance, but on closer look the high score is the result of four respectful reviews, and no dissent. As far as I'm concerned the album delivers the conceptual and lyrical goods, but technically isn't in the same league as, say, Meshuggah's ObZen (another Metacritic high score). Mind you, I doubt anyone is in the same league as Meshuggah, so Underoath have done themselves proud just by holding their own. Best Heard: while cleaning out the basement — alone (A).

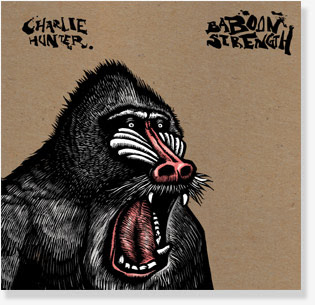

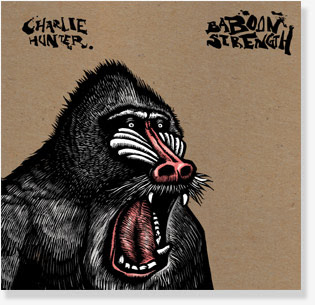

Baboon Strength by Charlie Hunter. Far and away my favorite album last month, which came to my attention thanks to 30 all-too-brief seconds when it qualified for eMusic's daily “Powerchart.” Hunter's album recalls the dance-infectious rhapsodizing of Medeski, Martin & Wood, while staying firmly inside the pocket. It's trippy Space: 1999 fun — a progressive revelation as well as a delightful throwback to what made T Rex such a hoot to listen to. Best Heard: while driving the car, 'cos it is The Antidote to simmering road rage. Not to be missed! (e, A)

Websites: Dr. Dog, Buddy Miller, Underoath, Charlie Hunter.

Fate by Dr. Dog. I hadn't heard of these guys until DV assured me they are all the rage among the younger crowd, particularly in Philly. Despite my initial misgivings, I quickly became fond of Fate. I won't try to emulate this guy's Bangsian endorsement (I'm not that enthusiastic of the disc, for one thing): better just to resort to lazy typifying. Dr. Dog gains their musical traction via the disciplined harmonic experimentation The Beatles liked to do, coupled with the lyrical and percussive play the Talking Heads enjoyed. My daughters found the overarching effect a little melancholy, but nowhere near to the degree of an act like Wilco (I confess I don't really get those guys). Best Heard: while prepping food on a sunny afternoon (e, A).

Fate by Dr. Dog. I hadn't heard of these guys until DV assured me they are all the rage among the younger crowd, particularly in Philly. Despite my initial misgivings, I quickly became fond of Fate. I won't try to emulate this guy's Bangsian endorsement (I'm not that enthusiastic of the disc, for one thing): better just to resort to lazy typifying. Dr. Dog gains their musical traction via the disciplined harmonic experimentation The Beatles liked to do, coupled with the lyrical and percussive play the Talking Heads enjoyed. My daughters found the overarching effect a little melancholy, but nowhere near to the degree of an act like Wilco (I confess I don't really get those guys). Best Heard: while prepping food on a sunny afternoon (e, A).

Universal United House of Prayer by Buddy Miller. This is a spinach 'n grits album — it's delicious, but has a robustness that can be unsettling. Miller opens the album with a Mark Heard song that pretty much sums up the last eight years (well ... the last 30, really) of my life: “Worry Too Much.”

It's the quick-step march of history

The vanity of nations

It's the way there'll be no muffled drums

To mark the passage of my generation

It's the children of my children

It's the lambs born in innocence

It's wondering if the good I know

Will last to be seen by the eyes of the little ones

Miller launches from here into a sincere exploration of his faith, the parameters of which are familiar — and discomfiting — to me. Miller's vehicle of choice is what Pappy O'Daniel calls “Old Timey Music”: I do love this disc, but find it difficult to listen to. The songs, the sentiment and dare I say the faith are all sturdy enough to deliver Miller from the present crucible of life, but I could have done with just a dash of “O'Daniel's” conniving guile. A little whisky makes the preaching easier to ingest. Best Heard: when tempted to YouTube Sarah Palin (e, A).

Lost In The Sound Of Separation by Underoath. Metal has splintered into so many different discordant shards I have a very difficult time keeping track of what's worth listening to. Unless a friend passes along a disc, or Metacritic tabulates a particularly high mark, I don't even bother with the genre. Underoath qualifies in the latter instance, but on closer look the high score is the result of four respectful reviews, and no dissent. As far as I'm concerned the album delivers the conceptual and lyrical goods, but technically isn't in the same league as, say, Meshuggah's ObZen (another Metacritic high score). Mind you, I doubt anyone is in the same league as Meshuggah, so Underoath have done themselves proud just by holding their own. Best Heard: while cleaning out the basement — alone (A).

Baboon Strength by Charlie Hunter. Far and away my favorite album last month, which came to my attention thanks to 30 all-too-brief seconds when it qualified for eMusic's daily “Powerchart.” Hunter's album recalls the dance-infectious rhapsodizing of Medeski, Martin & Wood, while staying firmly inside the pocket. It's trippy Space: 1999 fun — a progressive revelation as well as a delightful throwback to what made T Rex such a hoot to listen to. Best Heard: while driving the car, 'cos it is The Antidote to simmering road rage. Not to be missed! (e, A)

Websites: Dr. Dog, Buddy Miller, Underoath, Charlie Hunter.

Monday, October 13, 2008

Re: Learning Guitar

Twenty years ago I figured out how to strum the guitar. I was also introduced to travis picking, along with a smattering of classical finger-picking. It was all strictly campfire technique, but since I had no shortage of campfires to attend I had a lot of fun with it.

My daughters are of the age where they are learning the usual gamut of instrument play. Listening to their tentative steps into a larger technique, I was finally inspired to pick up my old "How To" books and teach myself some much-needed basics, including reading music. I'm finally of the age where I don't bristle at plinking out "Hot Cross Buns" on a single string!

This does not pass as music to my daughters' ears. Said my younger to my wife: "You'd think he'd know how to play that thing by now."

Tangential self-promotion: this Thanksgiving has been a huge improvement on last year.

My daughters are of the age where they are learning the usual gamut of instrument play. Listening to their tentative steps into a larger technique, I was finally inspired to pick up my old "How To" books and teach myself some much-needed basics, including reading music. I'm finally of the age where I don't bristle at plinking out "Hot Cross Buns" on a single string!

This does not pass as music to my daughters' ears. Said my younger to my wife: "You'd think he'd know how to play that thing by now."

Tangential self-promotion: this Thanksgiving has been a huge improvement on last year.

Tuesday, October 07, 2008

Elsewhere

I have had trouble putting my finger on just why I find McCain's cynical, sinister choice of Palin so incredibly infuriating-slash-depressing. Fortunately there is no lack of articulate people to fill in my silence. Links via bookforum.

"I don’t like categories like religious and not religious. As soon as religion draws a line around itself it becomes falsified. It seems to me that anything that is written compassionately and perceptively probably satisfies every definition of religious whether a writer intends it to be religious or not." The Paris Review interviews Marilynne Robinson (via Maude Newton).

So now we're all on Wall Street catching the grey men when they dive from the 14th floor*, and I'm thinking, "Where's George Soros? It's not like an economist -- even a retired one -- to be silent in times like these!" Indeed not.

And last, but by no means least, 20 massive indicators that the video game industry is trapped and sinking in a Sargasso Sea of onerous cliché. Speaking of which, I am compelled to say that playing The Simpsons has been one of my greatest disappointments in gaming. The Simpsons Hit & Run used the Grand Theft Auto engine to brilliant, satirical effect and was a hoot to play. But this latest chapter is just a mess, particularly in its gameplay, and wouldn't pass muster as a badly-written episode. The Onion was right.

"I don’t like categories like religious and not religious. As soon as religion draws a line around itself it becomes falsified. It seems to me that anything that is written compassionately and perceptively probably satisfies every definition of religious whether a writer intends it to be religious or not." The Paris Review interviews Marilynne Robinson (via Maude Newton).

So now we're all on Wall Street catching the grey men when they dive from the 14th floor*, and I'm thinking, "Where's George Soros? It's not like an economist -- even a retired one -- to be silent in times like these!" Indeed not.

And last, but by no means least, 20 massive indicators that the video game industry is trapped and sinking in a Sargasso Sea of onerous cliché. Speaking of which, I am compelled to say that playing The Simpsons has been one of my greatest disappointments in gaming. The Simpsons Hit & Run used the Grand Theft Auto engine to brilliant, satirical effect and was a hoot to play. But this latest chapter is just a mess, particularly in its gameplay, and wouldn't pass muster as a badly-written episode. The Onion was right.

Sunday, October 05, 2008

The "Hug & Kiss" Novel

Yesterday while I was frying crepes at the cafe a young co-worker told me of a book she'd just read. She waxed on about the profound effect the novel had had on her. I finally said, “It sounds to me like this was a Hug & Kiss Novel.”

She asked what that was, and I told her of an incident I'd experienced in university. I was walking the halls to my next engagement when I encountered a friend who surprised me by giving me a long, warm hug and concluding that with a kiss. Prior to this embrace I hadn't thought of my friend in amorous terms, and I somehow had the impression she hadn't given me any reason to change my thinking. “What was that for?” I asked.

“Oh, I just finished reading the most incredible book!”

And so a group of us began the Hug & Kiss Book Club, which had some of the same rules as Fight Club (we never talked about it) but none of the unpleasantness. We were touchy-feely boho-types, and most of us lived downtown. The odds of finishing a wonderful book and immediately encountering a friend were pretty good, so we gave the first friend we encountered a Hug & Kiss.

Many of the authors were the usual suspects. The friend who started this off had just finished reading The Book Of Laughter And Forgetting by Milan Kundera (A). Herman Hesse frequently inspired the Hug & Kiss. So did Paul Auster's Moon Palace, I Served The King Of England by Bohumil Hrabl, Crowley's Little, Big and poetry by Jim Harrison. Two weeks after I finished Don DeLilo's Underworld, I found myself sitting on a downtown bench and clearing the tears from my eyes because of a deluge of connections I'd just made. I was in my 30s now, and my friends had all moved on: there was no-one I could trust with the Hug & Kiss.

“That's it exactly!” said my co-worker. Her novel was Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels — a gorgeous, frequently heartbreaking and finally life-and-love-affirming book. “I fell in love amid the clattering of spoons....” Shapely material indeed for the Hug & Kiss (A).

As she enthused, I silently wondered what had happened to my Hug & Kiss impulse. I've read some beautiful novels since Underworld, and more than a few have brought tears to my eyes. But the effect isn't the same as it was in my 20s and early 30s. My guess is when we were younger we read in fear that our lives were constricting in predictable and not always welcome ways. The world surrounding us conspired in this constriction. These books were a wild affirmation of sorts, and we were young and flaky enough to respond physically.

Some of the novelists we encountered when we were younger have aged as well. It's not uncommon to discover that their current material acknowledges limits the younger novelist did not see. They have changed; we have changed. Our response changes in kind.

I've also become too much the Mennonite as I grow older — puritanically chaste in my physical contact with others. In my aversion to emotional complication I too frequently eschew physicality altogether. My loss. Others' too, I suppose.

The world continues to conspire and constrict. Fortunately there remain books that encourage openness. The last such for me was Marilynne Robinson's Gilead (A). I slowed down a bit after reading that, and tried to listen to the people who make me impatient. Not exactly a Hug & Kiss, but if the people around me were to be honest this was probably the more welcome response. Hugs are swell, to be sure, and no-one should discourage their practice. But listening is the real trick.

If I ever get the secret to listening, I'll pass it along. In the meantime, I'll keep reading. And if properly nudged I may even return to the Hug & Kiss.

Endnotes: Here are my thoughts on Moon Palace. Here, Gilead.

She asked what that was, and I told her of an incident I'd experienced in university. I was walking the halls to my next engagement when I encountered a friend who surprised me by giving me a long, warm hug and concluding that with a kiss. Prior to this embrace I hadn't thought of my friend in amorous terms, and I somehow had the impression she hadn't given me any reason to change my thinking. “What was that for?” I asked.

“Oh, I just finished reading the most incredible book!”

And so a group of us began the Hug & Kiss Book Club, which had some of the same rules as Fight Club (we never talked about it) but none of the unpleasantness. We were touchy-feely boho-types, and most of us lived downtown. The odds of finishing a wonderful book and immediately encountering a friend were pretty good, so we gave the first friend we encountered a Hug & Kiss.

Many of the authors were the usual suspects. The friend who started this off had just finished reading The Book Of Laughter And Forgetting by Milan Kundera (A). Herman Hesse frequently inspired the Hug & Kiss. So did Paul Auster's Moon Palace, I Served The King Of England by Bohumil Hrabl, Crowley's Little, Big and poetry by Jim Harrison. Two weeks after I finished Don DeLilo's Underworld, I found myself sitting on a downtown bench and clearing the tears from my eyes because of a deluge of connections I'd just made. I was in my 30s now, and my friends had all moved on: there was no-one I could trust with the Hug & Kiss.

“That's it exactly!” said my co-worker. Her novel was Fugitive Pieces by Anne Michaels — a gorgeous, frequently heartbreaking and finally life-and-love-affirming book. “I fell in love amid the clattering of spoons....” Shapely material indeed for the Hug & Kiss (A).

As she enthused, I silently wondered what had happened to my Hug & Kiss impulse. I've read some beautiful novels since Underworld, and more than a few have brought tears to my eyes. But the effect isn't the same as it was in my 20s and early 30s. My guess is when we were younger we read in fear that our lives were constricting in predictable and not always welcome ways. The world surrounding us conspired in this constriction. These books were a wild affirmation of sorts, and we were young and flaky enough to respond physically.

Some of the novelists we encountered when we were younger have aged as well. It's not uncommon to discover that their current material acknowledges limits the younger novelist did not see. They have changed; we have changed. Our response changes in kind.

I've also become too much the Mennonite as I grow older — puritanically chaste in my physical contact with others. In my aversion to emotional complication I too frequently eschew physicality altogether. My loss. Others' too, I suppose.

The world continues to conspire and constrict. Fortunately there remain books that encourage openness. The last such for me was Marilynne Robinson's Gilead (A). I slowed down a bit after reading that, and tried to listen to the people who make me impatient. Not exactly a Hug & Kiss, but if the people around me were to be honest this was probably the more welcome response. Hugs are swell, to be sure, and no-one should discourage their practice. But listening is the real trick.

If I ever get the secret to listening, I'll pass it along. In the meantime, I'll keep reading. And if properly nudged I may even return to the Hug & Kiss.

Endnotes: Here are my thoughts on Moon Palace. Here, Gilead.

Thursday, October 02, 2008

My Favourite Newman Role

Reggie Dunlop, in Slap Shot (W).

Yeah, we all throw accolades at Paul Newman for the humanity he brought to The Hustler, Hud and Cool Hand Luke. He deserves them. And while I have not seen every film Newman made, I doubt he ever played a more reprehensible character than Reggie Dunlop.

Yeah, we all throw accolades at Paul Newman for the humanity he brought to The Hustler, Hud and Cool Hand Luke. He deserves them. And while I have not seen every film Newman made, I doubt he ever played a more reprehensible character than Reggie Dunlop.

The movie's script, storyline and pacing are a complete hash -- the sort of scrambled-eggs-for-the-hangover project that would never get green lighted by today's studios, but was the standard for the 70s. Slap Shot is a choppy exercise at best, but oy! does it ever stick to the brain cells. It's lewd, crude, degenerate, unreflective and unrepentant, and at the center is Newman's Dunlop, who embodies all these traits to perfection. One gander at that picture reveals exactly what Newman brought to the set: a man whose body was too old to play decent hockey and whose personality was too locked-in by Type-A (for "Adolescent") cunning to be decent about anything.

Reggie Dunlop is an awful man (language warning!). And the fact that I didn't want to miss a single second of Newman's performance in this film is a tribute to his remarkable capacities as an actor.

Yeah, we all throw accolades at Paul Newman for the humanity he brought to The Hustler, Hud and Cool Hand Luke. He deserves them. And while I have not seen every film Newman made, I doubt he ever played a more reprehensible character than Reggie Dunlop.

Yeah, we all throw accolades at Paul Newman for the humanity he brought to The Hustler, Hud and Cool Hand Luke. He deserves them. And while I have not seen every film Newman made, I doubt he ever played a more reprehensible character than Reggie Dunlop.The movie's script, storyline and pacing are a complete hash -- the sort of scrambled-eggs-for-the-hangover project that would never get green lighted by today's studios, but was the standard for the 70s. Slap Shot is a choppy exercise at best, but oy! does it ever stick to the brain cells. It's lewd, crude, degenerate, unreflective and unrepentant, and at the center is Newman's Dunlop, who embodies all these traits to perfection. One gander at that picture reveals exactly what Newman brought to the set: a man whose body was too old to play decent hockey and whose personality was too locked-in by Type-A (for "Adolescent") cunning to be decent about anything.

Reggie Dunlop is an awful man (language warning!). And the fact that I didn't want to miss a single second of Newman's performance in this film is a tribute to his remarkable capacities as an actor.

Will Eisner's The Spirit

Drawn! links to these 12 fab splash pages illustrating (and explicating) some of the genius behind Will Eisner's The Spirit. Even though the posting is entitled 12 Splash Pages Will Convince You Frank Miller Shouldn't Adapt The Spirit, io9 graciously concludes, "The bar is set high, but it's always enjoyable to watch a confident director adapt deserving material." Comic book fans are usually the most hesitant when it comes to embracing silver-screen adaptations -- I have my own reservations about Miller -- but a property that is as nuanced as The Spirit poses particular challenges, as this person makes clear.

Johnny LaRue's Cure-All

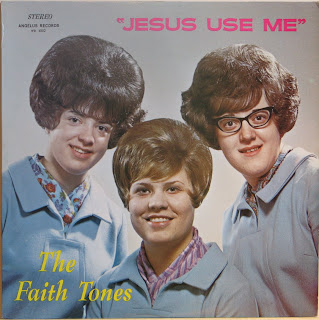

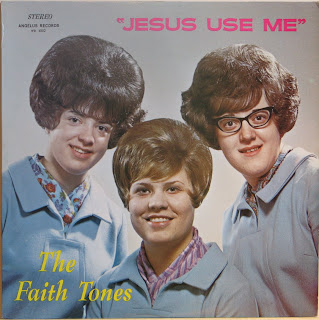

The last few posts seem to find me sinking in a religious direction. As Johnny LaRue used to say, "The only way to cure a hangover is with more booze." Who am I to argue? Seeker-friendly BoingBoing provides 100-proof medicine:

There doesn't seem to be any accompanying video featuring this trio, but I'd say this is a worthy substitute (warning: you WILL be humming this tune for the rest of the day):

Wow. Somehow, in my mis-spent youth, I never caught wind of these guys. Ah, but it's never too late to have a happy childhood.

Prairie Mary is also thinking about religion. As ever her approach is thoughtful and provocative -- but you probably won't be humming when you leave her blog.

And, of course, there is always The Ramones:

There doesn't seem to be any accompanying video featuring this trio, but I'd say this is a worthy substitute (warning: you WILL be humming this tune for the rest of the day):

Wow. Somehow, in my mis-spent youth, I never caught wind of these guys. Ah, but it's never too late to have a happy childhood.

Prairie Mary is also thinking about religion. As ever her approach is thoughtful and provocative -- but you probably won't be humming when you leave her blog.

And, of course, there is always The Ramones:

Wednesday, October 01, 2008

Rattling In My Brain Pan

The weekend edition is usually the only paper I bother with, and of my immediate choices I usually go with Toronto's national newspaper The Globe & Mail. This weekend their headlines were no different from any other paper, but there were a few oddities tucked into the margins that are still rattling in my brain pan. To wit:

An epistolary exchange between Ian Brown (journalist) and Jean Vanier (founder of L'Arche community). Vanier is one of those rarities: when he speaks of matters of faith, people don't usually try to drown him out with objections and ridicule. This doesn't prevent Brown from frank disclosure of his doubts and frustrations, however. With the whole world just itching to descend on Wall Street with torches and pitchforks, this is a very welcome conversation to attend.

Just over a year ago I tried to read and wrap my head around This Is My Country, What's Yours? A Literary Atlas Of Canada by Noah Richler (A). I couldn't do it. This was due in no small part to my impatience with any and all literary theory, particularly "big" theory. If I understand the early argument of Richler's book, it's that the novel is a technology that has transformed Western society and much of the world for better and for worse. Richler and his interviewees explore the different avenues through which this has occurred, and some of these proposals struck me as more likely than others. This is a moral argument, of course, and within the storm of this book is the quiet subtext of Richler himself, hoping for better literature and a society of attentive readers.

Perhaps I need to begin a dialog with Richler, because my faith in such matters is extremely weak. So many of the world's most accomplished novelists are insufferable assholes at best, cruel tormentors at worst. Their art is incapable of transforming the artist: what hope does it have of transforming the culture? In order for me to get any writing done I have to work very hard at setting aside such concerns and focusing instead on the art of transmission: this is how it feels for the character -- do you feel it too? It could be there is something mystical and even holy involved in the act of such focus, but I balk mightily at such claims. Chalk that down to a paucity of my own imagination, even a damnable lack of nerve. So it goes.

Anyhow, these thoughts return to me as Richler reviews John Ralston Saul's A Fair Country: Telling Truths About Canada (A) which he asks the country's electorate to read before voting. Saul's method of getting to the heart of the matter is similar to Richler's (Richler, however, does considerably more physical footwork), making Richler the ideal reviewer for his material. The curious should read this interview with Saul to get some idea of what his concerns are, then move on to Richler's review.

An epistolary exchange between Ian Brown (journalist) and Jean Vanier (founder of L'Arche community). Vanier is one of those rarities: when he speaks of matters of faith, people don't usually try to drown him out with objections and ridicule. This doesn't prevent Brown from frank disclosure of his doubts and frustrations, however. With the whole world just itching to descend on Wall Street with torches and pitchforks, this is a very welcome conversation to attend.

Just over a year ago I tried to read and wrap my head around This Is My Country, What's Yours? A Literary Atlas Of Canada by Noah Richler (A). I couldn't do it. This was due in no small part to my impatience with any and all literary theory, particularly "big" theory. If I understand the early argument of Richler's book, it's that the novel is a technology that has transformed Western society and much of the world for better and for worse. Richler and his interviewees explore the different avenues through which this has occurred, and some of these proposals struck me as more likely than others. This is a moral argument, of course, and within the storm of this book is the quiet subtext of Richler himself, hoping for better literature and a society of attentive readers.

Perhaps I need to begin a dialog with Richler, because my faith in such matters is extremely weak. So many of the world's most accomplished novelists are insufferable assholes at best, cruel tormentors at worst. Their art is incapable of transforming the artist: what hope does it have of transforming the culture? In order for me to get any writing done I have to work very hard at setting aside such concerns and focusing instead on the art of transmission: this is how it feels for the character -- do you feel it too? It could be there is something mystical and even holy involved in the act of such focus, but I balk mightily at such claims. Chalk that down to a paucity of my own imagination, even a damnable lack of nerve. So it goes.

Anyhow, these thoughts return to me as Richler reviews John Ralston Saul's A Fair Country: Telling Truths About Canada (A) which he asks the country's electorate to read before voting. Saul's method of getting to the heart of the matter is similar to Richler's (Richler, however, does considerably more physical footwork), making Richler the ideal reviewer for his material. The curious should read this interview with Saul to get some idea of what his concerns are, then move on to Richler's review.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)