Being a member of Trudeau Generation, receiving my education from the church and CBC, an awareness of Carr was deeply embedded within my consciousness. Not so my daughter, however, so this introductory exhibit came at an ideal time: at the crest of a teacher's strike. Off to the city we went.

From The Forest To The Sea is well-executed -- a brisk tour of Emily Carr highlights, peppered with well-chosen arcana to draw out a nuanced sense of the woman's character, inquisitiveness, even bitchiness.

I could have stood to see a bit more of the latter, frankly. Carr evidently had quite the life-force. In her later years her neighbors regarded her as an off-putting kook -- the old gal with a penchant for donning a hairnet and walking her assortment of pets in a pram. The curators took pains to prevent this late-in-life behavior from becoming the definitive portrait of Carr. Which led me to wonder: when did the Eccentric Artist cliche become a liability?

Another curatorial tic that induced me to eye-rolling: an apologetic stance toward her "cultural appropriation" of indigenous artifacts -- via her (voluminous) portraiture of totems, masks, and the like.

To be fair, our contempo cultural babysitters took pains to present Carr's penchant for "speaking on behalf of my Indian brothers" (her words) within the context of the times. At the turn of the 20th century, official government policy regarding the country's First Nations required absolute assimilation -- children who didn't fall to malnutrition or the plagues of the day were rounded up and deposited in residential schools, while totem poles and canoes were physically appropriated and shipped to approved cultural institutions, or simply destroyed. Carr responded with outspoken horror and defiance, devoting herself to portraiture of the disappearing totems in a personal effort to keep the artform alive -- a person, a woman, whose moral sense was out of sync with her time. That she was too obsessed/obtuse to note any misgivings the people she was keen to "save" might have had toward her enterprise is hardly surprising. One shudders to think what virtues our grandchildren will be apologizing for in three generations' time.

That being said, the display as curated was a personal revelation.

Two late-mid-career works, Indian Church and Wood Interior, are presented as keys to the larger body. It's an astute bit of positioning.

|

| The Indian Church, 1929 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wood Interior, 1929-1930 |

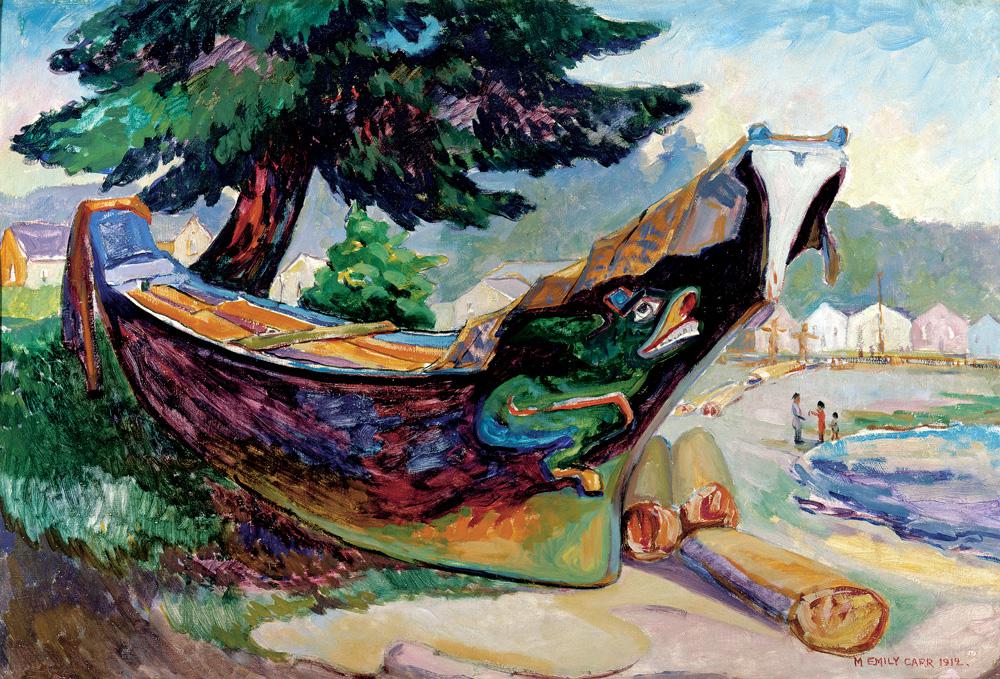

Seeing these pieces first does have an unsettling effect on the rest of the exhibition. The earlier pictures and mock-ups of "Indian" artifacts make up the bulk of the show -- and this exhibition presents just a well-culled sliver of her vast collection. Many of her most recognizable pieces are there, as well as the lesser attempts that lead up to these triumphs. After a while, it gets to be a bit much. "Really, Emily: another canoe?"

|

| "I mean, it's beautiful and all, but..." |

I imagine her friends among the Group of Seven must have felt some of that. Late in life, Lawren Harris apparently gave Carr a hard nudge to focus exclusively on landscape. And it is these final paintings of Carr's that resonated most deeply with me. She shifts into a mode strongly reminiscent of Van Gogh -- somewhat surprising, given how she was, at this late point in her life, happy to remain ignorant of artists she'd not actually met.

In a landscape like Stumps and Sky (1934), I got the sense that this clear-cut forest is releasing an anarchic apocalyptic energy to the four winds.

Similarly, my personal favourite, An Upward Trend (1937), which viscerally communicates what our very elderly often speak of: a perceived internal prompting to exceed the limits of the sky.

Sounds New Agey, I know. I expect Carr would have fostered the expectation, then crustily asserted she was no such thing, dammit.

The kid enjoyed Carr's early sketchbooks, tiny things with incredibly articulate pen-work.

|

| Presented here in an artfully-rendered crappy phone shot. |

From The Forest To The Sea is at the AGO from now until August 9, 2015. Bonus: until May 10, you can also check out this sassy Basquiat exhibit.

No comments:

Post a Comment